The Roots of Intersectionality

By SON Council for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

The following essay appears in our Fall 2022 Council for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (CoDEI) newsletter.

As part of our 2022 goals, CoDEI has selected to focus on the topic of intersectionality to help us address how our event planning, education, and overall work can include the concurrent existence of intersecting identities and an understanding of the systemic oppression individuals experience as a result of the social tensions concerning race, class, gender identity and expression, nationality, religion, sexual orientation and other historically minoritized identities.

Intersectionality is a commonly used phrase; however, it is often unintentionally used incorrectly when simply applied to the existence of our varied identities without reference to the existence of oppression that generate the ways individuals can exist as how author and activist, Alice Wong terms, “multiply marginalized.”

As with any concept there is a history to its origins that can provide us a broader context to deepen our awareness.

The Roots of Intersectionality

The origin of intersectionality is attributed to the work of civil rights scholar and activist, Kimberlé Crenshaw, professor of law at Colombia University and University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). As a practicing attorney Crenshaw was inspired to investigate the “intersecting, disadvantaging factors” that materialized in legal cases that addressed discrimination. In her 2016 TedTalk, The Urgency of Intersectionality, Crenshaw describes a specific case that contributed to her conceiving the metaphor of an intersection; further establishing intersectionality as a framework for analysis. This case involved a Black woman who had applied for work at a car manufacturing plant but was denied. She claimed the organization refused to hire her because she was a Black woman, however the court decision upheld the organization’s claim that it did not discriminate against her because they hired Black people and they hired women.

However, as Crenshaw explains, using intersectionality as an analytical framework reveals that while the organization did hire Black people for mechanical, technical positions, they only hired Black men. Similar to their claim in hiring women, they only hired White women for clerical positions. As Crenshaw’s analyzes, the court failed to entertain how these seemingly distinct issues of discrimination affected the plaintiff of the case, because they were unwilling and unable to recognize the manner in which these issues had overlapping impacts on the lives of Black women across both race and gender.

"As CoDEI continues planning events and educational opportunities we commit to applying an intersectional lens to the ways our actions and activities can be expansive and fully recognize the ways identities are complexly interwoven within the human experience."

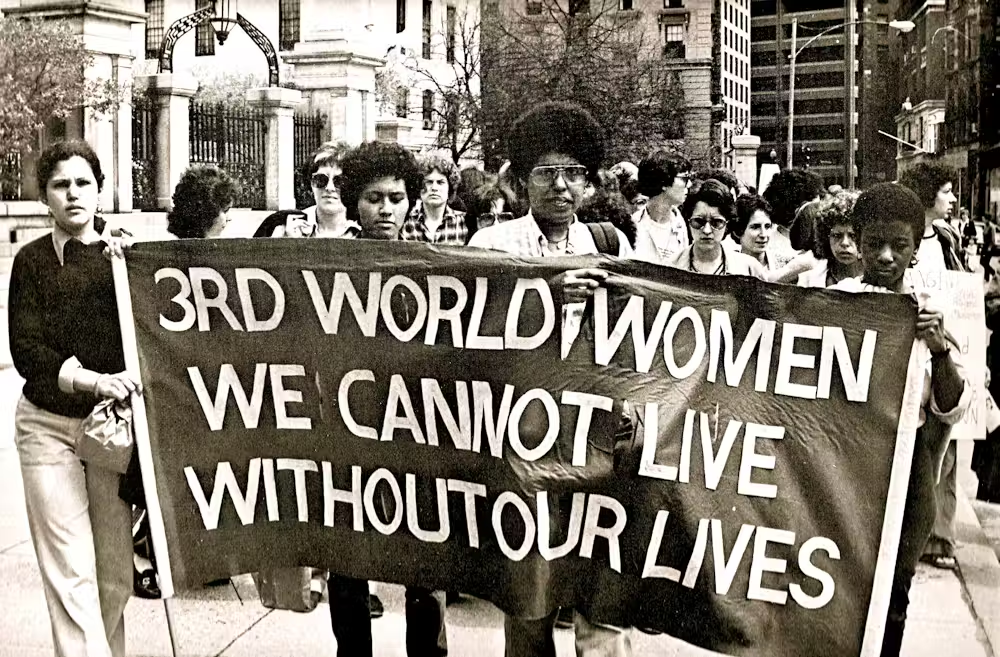

While Crenshaw is credited for the initiating the term intersectionality, the phenomenon of intersecting identities and oppressions was a point of contention within the feminist movement, leading to the evolution of Black and Third World feminism. In 1974, two decades before Crenshaw’s conception of the term intersectionality, three Black, queer women formed the Combahee River Collective and in 1977, generated a statement in response to the alienation that Black women experienced within White feminist organizations who refused to take up issues that disproportionately affected Black communities. In addition, the statement’s authors, sisters Barbara and Beverly Smith, and Demita Frazier, addressed the way cis-gender, male dominated, Black liberation movement failed to take up the “interlocking oppressions” of racism, sexism and heteronormativity that affected their unique experiences not only as Black woman, but as lesbians In the statement they state, “….we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see our particular tasks the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking.”

While the Combahee River Collective statement addressed the specific needs of Black women, its authors recognized the interconnectedness between Black liberation and the liberation of all minoritized folks throughout the world. This global perspective is further emphasized in Patricia Hill Collins and Sirma Bilge’s book, Intersectionality, in which they explicate its use as an analytic tool through critical inquiry and praxis (the integration of theory into practice). Using examples from the politics and power dynamics of the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA), Collins and Bilge identify the effects that different domains of power: structural, cultural, disciplinary, and interpersonal, have upon multiple identity dimensions.

For example, in demonstrating the impact of structural domain of power, Collins and Bilge compare how the legal and economic protections afforded to the FIFA organization provides the organization certain financial protections under the designation as an NGO even as it functions as a private corporation. The organization’s assertion of power includes its ability to influence the policies and fiscal priorities of countries selected to host the World Cup, often deterring the capacity of certain developing countries to sustain the social systems needed for all its citizenry to thrive by accessing necessary resources like health care, education, or even clean water. Using an intersectional analysis, the authors identify how the national decisions and priorities of host countries, imposed upon by FIFA’s regulations, contributes to governmental corruption that impacts the country’s most vulnerable populations across nationality, gender, race, and class.

Another example Collins and Bilge provide to elaborate the disciplinary power domain, are the FIFA’s rules of play designating who is permitted to be a successful athlete. Using an intersectional analysis, Collins and Bilge reveal the ways these rules are created to support the organization’s ability to generate a profit from the athletes’ labor. These rules of play in turn create barriers based on who can afford to pursue their training, have access to equipment, including the persistent gender pay disparities that differentiates among nation states. In the addition of gender discrimination, some female players confront the perceived value of their ability to play the game. For instance, while European and American female players struggle for equitable pay, they are able to earn a salary as an athlete. Meanwhile, female players in Nigeria are given a government sanctioned stipend for the equipment to play rather than earning a salary as a player. The constraints of these rule also affect male athletes of color who join Western European teams only to confront racist behavior from the fans.

These examples, when examined with an intersectional lens, further emphasize how the complexities between human identities and the obstacles generated from systemic manifestations of inequities, cannot be understood through the conventional means of addressing racism, feminism, classism or any form of oppression, as linear incidents. Intersectionality permits us to recognize the multiple ways people exist as an amalgamation of their relationships with history, the environment, institutions and systems, other people, ideas and values.

As CoDEI continues planning events and educational opportunities we commit to applying an intersectional lens to the ways our actions and activities can be expansive and fully recognize the ways identities are complexly interwoven within the human experience.

Categories: Community