In the Name of Pride

By Kristin Hocker

Thursday, July 27, 2023

This poster was seen during the New York City Pride events this past June. It features an image of the Black transgender icon, Marsha P. Johnson, wearing a crown of flowers and smiling. Above her portrait are bold letters that say, “MISSING”, and underneath her image, the caption says, “From your kids’ history books.” The link listed on the bottom is for Historicons, a site that features historical games for children.

This poster was seen during the New York City Pride events this past June. It features an image of the Black transgender icon, Marsha P. Johnson, wearing a crown of flowers and smiling. Above her portrait are bold letters that say, “MISSING”, and underneath her image, the caption says, “From your kids’ history books.” The link listed on the bottom is for Historicons, a site that features historical games for children.

The sentiment of this poster embodies a plethora of events that have occurred throughout the year; the pushback on anti-racism and anti-discrimination in the form of censuring education and banning books that emphasize our human diversity, in addition to the rampant anti-trans legislation being passed and challenged in several states.

This poster also stokes a form of curiosity similar to what scholar, Robin D.G. Kelley, would identify as freedom dreams, an audacity to envision what our communal experience could be if we allowed ourselves to become a transformative society, committed to actively upholding equity, justice, and liberation for all its citizens. It inspires a curiosity that wonders how our society could move past its resistance to learn all the stories within our history, including those of notable players who refused to be pushed to the margins, so that we as Bryan Stevenson states, may engage in reconciliation and restoration.

That curiosity leads us to wonder what would it mean to fully address, with humility, why our national aspirations of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, have not been fully extended to everyone. If being an American is really about living a dream, why have some of our fellow citizens experienced it as a living nightmare? What would it take for us to collectively examine these questions from the perspective of our social responsibility, rather than as some notion of individualized failures? And lastly, how might we examine these questions even as they create discomfort within us, and recognize that discomfort’s potential to fuel our growth and our capacity to thrive, both individually and socially?

With those questions in mind, this newsletter presents a brief narrative of an otherwise extensive history of Pride and LGBTQ+ liberation, including the notable actors who refused to be pushed to the margins and challenged this nation to reconsider how it practices the values it espouses.

It is important to note that this narrative will include some outdated language, which at the time had a specific context or was how an organization or individuals referred to themselves. Many of the terms used (e.g.: homosexuality, homophile, transvestite) have since evolved and fallen out of use.

It is important to note that this narrative will include some outdated language, which at the time had a specific context or was how an organization or individuals referred to themselves. Many of the terms used (e.g.: homosexuality, homophile, transvestite) have since evolved and fallen out of use.

Pride is More than a Month

On the surface, celebrating LGBTQ+ Pride can appear as though it is just a series of events that unfold during June (internationally), July (in Rochester and other cities), and September (the celebration of Black Pride in Rochester).

But Pride is more than that: Pride is a movement that encompasses an extensive history of LGBTQ+ liberation and resilience. This history includes the diligent commitment of advocates, organizations, legislators, community organizers, students, actors, artists, scientists, and educators; a countless variety of human beings challenging the dominant narrative, fighting for justice, and the acknowledgment, respect, and affirmation of their humanity.

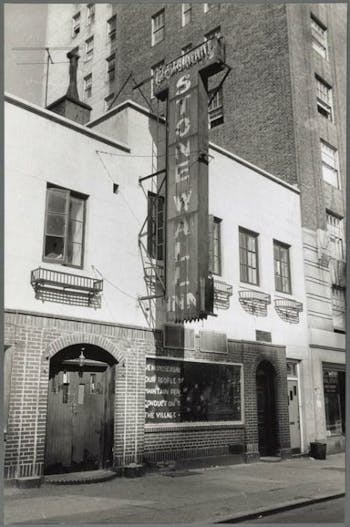

You may recognize the common catchphrase, “The first Pride was a Riot”, associating this perpetual movement with the infamous events at the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969. However, the history of this movement in the United States is broader than that significant moment.

The Society for Human Rights

Like many European immigrants before him, Henry Gerber arrived at Ellis Island in 1913 from Bavaria. He eventually made Chicago his home, due to its vibrant German population. During WWI, Henry was interned; deemed an enemy due to his German origins. When the war ended, he served in the U.S. Army of Occupation of Germany where he encountered an open and progressive scene that embraced homosexuality. Members of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (S-HC), an activist group founded by neurologist and researcher of human sexuality, Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, worked to override persecution of sexual and gender-variant minorities throughout Europe. More specifically, they sought to overturn Paragraph 175 and decriminalize sexual activity between gay men.

Inspired by the examples of gay activism he witnessed in Germany, Gerber returned to Chicago, and withJohn T. Graves, a Black minister, they established the Society for Human Rights, the first gay rights organization in the United States. Members of the Society for Human Rights worked to roll back sodomy laws in an effort to prevent people from being arrested, charged, and having to serve time in prison and contend with the broader implications those charges had on their lives.

Unfortunately, the German activists that inspired Gerber found themselves confronting state-sanctioned violence as a result of Hitler’s ascension to power as Chancellor of Germany in 1933. The rise of the Nazi party enabled the tyrannical enforcement of Paragraph 175, which persecuted gay-identified folks, including sending them to concentration camps. Dr. Hirschfeld’s research was destroyed by a Nazi student group who demolished his Institute and set his books and papers ablaze during a public book burning. This violent climate forced Dr. Hirschfeld, among others, to escape and to live in exile.

Back in the U.S., the Society for Human Rights experienced a brief existence (1924-1925) that ended with a police raid in which Gerber was arrested. However, while the Society disbanded, their work persisted underground. At the end of WWII, a new chapter of this perpetual movement emerged, called the Homophile Movement.

The Homophile Movement

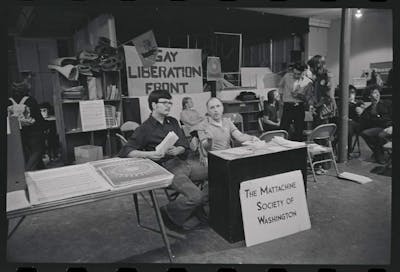

The Homophile Movement signifies an array of independent groups that emerged throughout different cities across the United States. Groups such as the Mattachine Foundation was started by Henry Hay in Los Angeles in 1950, but eventually dispersed into several branches in different U.S. cities, becoming the Mattachine Society. In San Francisco, Rosalie “Rose” Bamberger, her partner, and three other lesbian couples founded the Daughters of Bilitis.

These groups served as social clubs for gay and lesbian individuals to be in affinity with each other and engage in acts of civil disobedience to advocate for their rights.

One of these acts was a “sip-in” at Julius Bar. In 1966, three members of the Greenwich Village Mattachine Society walked into the bar, stated they were gay, and ordered drinks. They were subsequently denied service. This “sip-in” was inspired by the sit-ins of the Civil Rights movement, where Black students occupied lunch counters in the South, were denied service, and nonviolently endured hostility from the staff and patrons. In New York City, bars like Julius were permitted to discriminate against patrons they deemed were gay, by determining if patrons were engaging in orderly conduct. Any bar caught serving someone who was gay or perceived as gay risked having their liquor license revoked. While there were gay bars, those bars were frequently targeted with police raids that forced them to pay fines, rendering them vulnerable to being shut down. Which brings us to the most recognized chapter of LGBTQ+ history, Stonewall.

Stonewall

Stonewall

The phrase, “The first Pride was a Riot” was popularized after Hollywood attempted to recreate those events in 2015, and in 2019, when the U.S. celebrated Stonewall’s 50th anniversary.

Yet as journalists and historians set about documenting what happened that evening, several myths and legends were unraveled; from the myth about people gathering to mourn Judy Garland’s passing to postulating who threw the initial bricks or shot glasses. Uncovering the truth also revealed controversy about how events of that evening are referenced. Was it a riot, an uprising, or a rebellion?

The debate concerning this mythos does not diminish the significance of Stonewall. Whether it is called a riot, an uprising, or a rebellion, Stonewall was a catalyst in this extensive history of LGBTQ+ activism and liberation, because that evening was a manifestation of LGBTQ+ resistance, countering the police raid, with culminated frustration and anger from being targeted, brutalized, and criminalized for openly being themselves and wanting to live freely, including the freedom to enjoy a drink at a local bar. The fires at Stonewall sparked the ongoing activism that birthed the Gay Liberation Front, the Gay Activists Alliance, and other LGBTQ+ organizations that emerged throughout the U.S. and around the world.

Unraveling the myths of Stonewall includes recognizing the roles of Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, two transgender women of color who are often attributed to playing a major role in Stonewall. While they both shared in interviews that they were present that evening, they also shared that they were not the key perpetrators of the resistance as the stories convey. Silvia Rivera famously states, “I did not throw the first Molotov cocktail, but I did throw the second.” Regardless of their direct or indirect interaction with the events at Stonewall, their historical contributions are monumental.

Marsha P. Johnson and Silvia Rivera

Marsha P. Johnson and Silvia Rivera

Before becoming historical icons, Marsha and Silvia were friends. As the elder of the two, Marsha helped Silvia navigate being a trans woman in a world hostile to gender diversity. Marsha operated from her living mantra, which also served as advice for others concerned about her gender identity and expression, “pay it no mind.” This expression was signified by the P in her name.

After Stonewall, Marsha, and Silvia participated in the Gay Liberation Front but found their voices and perspectives as trans women of color were overshadowed by the predominantly White gay and lesbian members, who failed to recognize the needs of transgender people. This was evident when Silvia and Marsha, and other trans folks were excluded from the initial pride parade in 1970, and in 1973, Silvia was asked to participate but told not to speak.

Marsha and Silvia recognized that transgender folks were the most vulnerable to inequity. They were frequent targets of police brutality and experienced the highest rates of homelessness due to discriminatory policies and mistreatment. In 1970, they organized the Street Transvestite Activist Revolutionaries (STAR), to provide safe haven and support to trans and gender non-conforming individuals who often found themselves without a home. While STAR was able to maintain a physical space for a short period of time, unfortunately, Marsha and Silvia were unable to pay rent and were evicted. Yet despite losing their physical space they continued providing support.

Throughout her lifetime, Marcia provided shelter, clothing, and support to others, and was known as “Saint Marcia,” however she would spend most of her life homeless needing to hustle for money to survive. In July 1992, her body was found in the Hudson River. Despite the police’s claim that her death was by suicide, those who loved her suspected that her death was the result of an attack, given the rate of trans women of color who were attacked, a dismal trend that persists today. In 2012, the New York City Police Department reopened her case.

Silvia had left New York City and activism but returned to both after Marsha’s death. In 1997 she took up residence in Transy House, a communal space and safe haven established by trans women, Rusty Mae Moore and Chelsea Goodwin, who modeled it after STAR. Silvia was honored during the 25th-anniversary Stonewall Inn march and continued marching in Pride parades until 2001.

Silvia passed away from cancer in 2002. Her work continues through the Silvia Rivera Law Project. In 2015 she became the first transgender American to be included in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

In 2019, Marsha was posthumously granted the honor of grand marshal for the New York City Pride parade. That same year, trans activist Elle Moxley, initiated the Marsha P. Johnson Institute, a Black, trans-led organization to continue Marsha’s life work, supporting, advocating, and defending the rights of trans women of color. On February 2021, officials renamed East River State Park, the Marsha P. Johnson State Park.

Looking Back to Move Forward

This brief summary of the longstanding origins of Pride, and the manifestations of advocacy and liberation, only scratches the surface of LGBTQ+ history that is essentially U.S. history; the stories of all of us. Yet, as we look back, it is imperative to recognize that this history goes even further when we consider that before Gerber and Graves opened the Society for Human Rights before the Mattachine Society members engaged in a sip-in at Julius. Before the arrival of the first Africans in 1619 and William Dorsey Swann became the first known drag queen to host drag balls. Before there were “founding fathers”, or the first ships from Europe arrived in Hispaniola. Before all that we’ve been told were our nation’s origins, the original occupants of this land recognized and embraced Two Spirit (also seen as 2S) people, members of the community who embodied gender fluidity in the roles, dress, and mannerisms they assumed. Prior to colonization, Two Spirit people were traditionally revered in Indigenous communities until centuries of Euro-centric values and norms were imposed upon them through the forced assimilation of colonization.

In Hawaiian culture, to be Māhū extends beyond a static identity and is not equivalent to being trans, or gender-diverse, it entails one’s responsibility to their community, culture, and ancestry. In pre-colonized Hawai’i, Māhū assumed essential roles as the keepers of traditional customs and practices and were responsible for passing them down to future generations. The Indigenous worldview that embraces Two Spirit individuals and Māhū as Eleisha Lauria states, “balanced human beings who express masculine and feminine with ease and freedom,” is a worldview that is being reclaimed by many Two Spirit people and Māhū today.

Freedom Dreaming

Hopefully, this opportunity to look back can inspire each of us to recognize the value of learning from our past without fearing its emotional impact. Perhaps we can gain new insight into the value of celebrating a community’s survival which included needing to reclaim their sense of self and a shared history of resistance against discrimination, dehumanization, and injustice. Perhaps as we look back on what we learn, it can encourage each of us to move forward and build a future that truly embodies the values of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that each and every one of us can fully enjoy.

This story appeared in the School of Nursing Council for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion's (CoDEI) July 2023 newsletter.