Diversity Feature: A History of Muslims in America

By Kristin Hocker

Thursday, April 28, 2022

An Extensive Story, Briefly Told

It is nearly impossible to capture the full essence of the rich, multifaceted, cultural identities of Muslims; identities that are shared with over two-billion people around the world, spanning multiple continents. Similar to how Christianity is divided across denominations (e.g., Episcopalian, Baptist, Catholic, Evangelical, etc.), Muslims distinguish themselves between denominations such as Sunni or Shia.

According to the Pew Research Center, the population growth among Muslims is increasing, and is predicted to grow faster than any other religious group by 2050. The Pew Research Center also calculated that an estimated 3.45 million Muslims live in the United States, making up 1.1% of the US population. Most notably, between 2007 and 2018, four Muslim American citizens were elected to Congress:

- Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minnesota),

- Rep. Andre Carson (D-Indiana)

- Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minnesota), first Muslim woman

- Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Michigan)

However, despite the growing numbers of Muslims in the United States, a 2019 survey reveals that 53% of Americans do not personally know anyone who is Muslim, while 52% stated they know nothing of Islam.

Origins of Islam

The origins of Islam are coupled with the origins of the Prophet Muhammed (peace be upon him). He was born in 570 CE, in what is now known as Mecca, in Saudi Arabia. Due to his parent’s deaths (father died before he was born, mother died when he was six), he was cared for by his paternal uncle. He then grew up and worked as a merchant.

In 611 CE, Muhammed experienced his first revelation in cave of Hira, where he often meditated. This would be the first of many revelations that would transform him into a Messenger of God. Several of his companions served as scribes who recorded his revelations and would then compile those revelations in the Qur’an, the Muslim holy text, after the prophet’s death. The Prophet Muhammed died in 632 CE, but Islam has spanned over 1,500 years and has persisted despite misperceptions, bigotry, and attempts to eradicate its practice.

Muslims visit the Hira cave where prophet Muhammed often meditated in on the top of Noor Mountain in Mecca.

The practice of Islam (which means “peace”), is to follow the example of the prophet by embodying the following Five Pillars of Islam:

- The profession of faith or shahada, by declaring the existence of one God, known as Allah, and the existence of his prophet, Muhammed.

- Prayer or salat, which occurs five times daily, while facing towards Mecca.

- Alms or zakat, which is an extension of one’s faith to provide for others as a form of mutual aid.

- Fasting, or sawm (also called sijam), which occurs during the holy time of Ramadan, from sunrise to sunset (if one is able).

- Pilgrimage or hajj, taking a pilgrimage to Mecca (one of the most famous accounts is documented in the book, The Autobiography of Malcom X).

First Wave: The Muslims among those Enslaved

As with any identity, Muslims are not a monolith, however as is often the case with misperceptions, they may be misconceived as a singular identity, such as in appearance or manners of worship, or even how they have arrived to the United States. Among the 5 million Muslims in the United States, over half of the population were born in the US, with 1/3 identifying as African American, 1/3 as Asian, 1/4 as Arab, and some as Latino/a/x.

Many are unaware that the history of the Muslim presence in the United States extends for 400 years, with the first arrival of enslaved people from West Africa, where Islam had been practiced since the 8th century, and is home to one of the world’s oldest universities, Sankore, erected by Muslim scholars in Mali in the 12th century. Additionally, in the 17th century Moriscos, former Muslims who were persecuted for their faith in Spain and Portugal, and settled in Spanish colonies and throughout what became the United States.

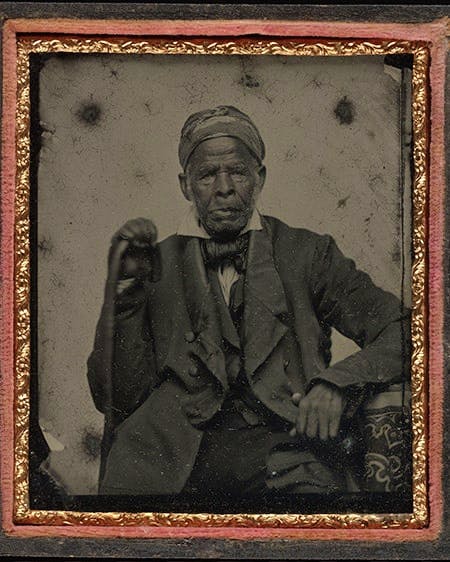

Unknown [Half length formal portrait of "Uncle Moreau" [Omar ibn Said];

elderly man seated wearing headwrap, suit;

left elbow rests on newel, cane in right hand. Ambrotype] (c. 1850).

Yale University Library.

One of the most notable Muslims who were enslaved was Omar ibn Said, who was born into the Fula tribe who occupied territory spanning from what is currently known as Senegal and Nigeria. While residing in Senegal, Omar ibn Said studied with Muslim scholars, including his brother, Sheikh Muhammed Said, and was eventually captured and sold into slavery in South Carolina. After an attempted escape, he ended up jailed in North Carolina, and began writing letters in Arabic. After his prison term ended, he resided in the household of John Owen, Governor of North Carolina, and composed his autobiography. Said’s autobiography is the only one to exist written by an enslaved person in Arabic. You may also find a collection of his writing archived at the Library of Congress.

Another is Ayuba Suleyman Diallo, who was abducted in 1739 from Gambia, and his written appeals for his freedom inspired assistance from James Oglethorpe, the eventual founder of the state of Georgia. Upon gaining his freedom, Diallo traveled to London, where he would meet the royal family and assist scholars with translating Arabic documents. He also wrote copies of the Qur’an from memory.

And Yarrow Mamout, who was enslaved from Guinea in 1752 at the age of 16, was first taken to Maryland, but eventually resided in Georgetown, in D.C. He remained a resident of Georgetown even after he was freed 44 years later. He then became a brick maker, a property owner, and financier, lending money to other merchants. He ultimately owned stock in the Columbia Bank of Georgetown.

Said, Diallo and Yarrow’s substantial scholarship and literacy gained the attention of their enslavers and captured the imagination of esteemed colonial notaries such as Thomas Jefferson and the National Anthem composer Francis Scott Key. While their lives became well-documented, the attention of their accomplishments and literary excellence unfortunately did little to sway the overwhelming regard among America’s colonizing class concerning the misperceptions of the intelligence of enslaved Africans.

Second Wave: Seeking Opportunity

From 1878-1924 a second wave of Muslims emigrated to the U.S. from the Greater Syria region, which includes Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and Palestine, in search of economic stability. Immigrants from this wave largely settled in the Midwest and established some of the oldest mosques in the U.S. as means for combating isolation and generating community, such as the North Dakota Mosque in Ross, North Dakota, established in 1924 and the Mother Mosque in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in 1934.

At the same time, African Americans were migrating up North during the Great Migration to escape the violence of the Jim Crow South while seeking better economic opportunities. Settling in their new cities, many African Americans rediscovered Islam within their ancestral roots. In Newark, New Jersey, Timothy Drew, known as Noble Drew Ali, established the Moorish Science Temple in 1913 for the purpose of teaching Black people about their Moorish origins and their Muslim identities, two things Ali claimed were taken from them during enslavement and racial segregation. Ali encouraged a practice of Islam rooted in Five Divine Principles – love, truth, peace, freedom, and justice, as a means for and uplifting African Americans by reclaiming their Black spiritual heritage.

Due to the firebrand nature of Malcolm X and Louis Farrakhan, people may be more familiar with The Nation of Islam (NOI); however, the NOI was a faction that split from the Moorish Science Temple in 1932, and established their base in Detroit, Michigan under the leadership of Wallace Fard. The NOI evolved under the leadership of a former sharecropper from Georgia who migrated to Detroit and became the Honorable Elijah Muhammed.

Third Wave: Further Opportunity and Hope

Several national as well as global factors precipitated a third wave of Muslim migration to the United States, such as Palestinian refugees who arrived after the creation of Israel in 1948, as well as immigration policy reforms generated from the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (McCarran-Walter Act), which expanded quotas (limits on how many people could enter from a specific country) and removed racial restrictions on citizenship by naturalization.

Additionally, the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart-Celler Act) overhauled US Immigration policy from 1920, thus ending de facto discrimination against non-European immigrants, facilitating an increase of immigration from all over the global South, greatly expanding the number of Muslim communities throughout the United States.

As historian Thomas Tweed (2004) states, “Muslims are more diverse than popular images allow and American Muslim history is longer than more might think.” (para 1).

"Muslims are more diverse than popular images allow and American Muslim history is longer than more might think."

While our common thread is always the fact that we are of the human species, learning about the rich, multifaceted ways in which we express our humanness provides us all an opportunity to humanize one another by acknowledging what makes each of us authentic.

As the literary and cultural critic Edward Said (1978/1994) reminds us, “Humanism is the only, I would go as far as saying the final, resistance we have against inhumane practices and injustice that disfigure human history."

Sharing this brief history is one way we can work towards that humanism. But dialogue, reading literature from the perspective and voice of someone else’s culture and identity, visiting spaces and places beyond our realities, are additional ways we can explore beyond the boundaries of our single stories, deepen our sense of inquiry and curiosity, and expand our understanding.

Islamic Contributions to Medicine

During the 7th century, as Islam extended across the world, Islamic scholars investigated the science of medicine by interpreting texts from Greece, Persia, and India into Arabic and Latin, as well as documenting their own scientific discoveries. At the time, the worldview in Europe, as influenced from the Catholic Church, professed that disease was a punishment from God.

However, the Islamic worldview was that disease provided an opportunity to solve a problem and assist people to heal. As a result, Muslim physicians and medical scholars discovered and initiated several techniques that are currently common practices, such as sanitation and wound cleaning. Scholars mapped the pathways of circulation in the body, and revealed other essential lessons of human anatomy and physiology. Islamic scholars also identified infectious diseases such as leprosy, smallpox and tuberculosis.

Mosque-sanctuary of Zaynab bint Ali (granddaughter of the Prophet Muhammad), the destination of Shiite pilgrimages (for healing)

This knowledge helped to inform the practice of several Muslim nurses who volunteered their healing services as medics during military campaigns, tending to the wounded and the infirmed. Among them was Zaynab bint Ali, granddaughter of the Prophet Muhammed (peace be upon him), who served as a field medic and whose courage and contributions are celebrated during Nurse’s Day in Iran.

Another notable nurse is Rufaida Al-Aslamiya, who was born in 620 AD. She was one of the first people to accept Islam in the city of Madina, and was among the Ansar women (“those who bring victory”) who greeted the Prophet Muhammed when he arrived to Madina. She learned medicine while assisting her father, a physician, and because she practiced her healing within the community she was not only known for her skills as a nurse, but as a social worker.

Despite originally being named Layla, Al-Shifa’ bint Abdullah gained her adopted name from her profession, with Al-Shifa meaning “the Healer.” Not only did she serve as a nurse, but she was a teacher of literacy as well as a business consultant, who often consulted the Prophet Muhammed. Al-Shifa was later appointed to the position of market inspector, which would be akin to being a health inspector today. She was the first Muslim woman to hold an appointed office.

Hocker is a faculty diversity officer and member of the Council for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusiveness. This story is a part of the Council for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion’s April newsletter. Learn more about the Council for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusiveness.